How a toy lawnmower started a parenting revolution

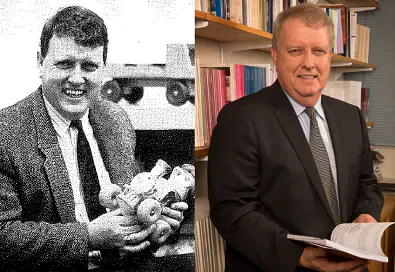

Q&A with Professor Matt Sanders

“Most people in this field want to do the right thing by families and get good results. But if you’re not using evidence-based programmes, you’re not using programmes that work – you’re hitting your head against a brick wall, frequently. You’re experiencing a lot of failure, clinically. And that’s demoralising.”

How would you describe your Triple P lightbulb moment?

“I did clinical practice for thirty years, seeing families every week. And there've been some pretty major moments that have led me to really re-think what we were doing with parenting. One of them I can recall was in the Behaviour Research and Therapy Centre, at the Royal Brisbane Hospital [Queensland, Australia] at that stage, running the clinic and talking to mother of a three- or four-year-old child who clearly had oppositional/conduct kind of problems.”

“And the child was in the room – I was just talking to the mother about how the week had been, and her experience of dealing with the child. The mother was talking, and the child was playing with this toy lawnmower. It was one of the worst toys you could ever have in a playroom, because “click-ka-click-ka-click-click” – it was a noisy darn toy anyway, and of course he was running around the room with this thing, and the mother started to talk about the concerns that she had with him. And the child just picked up the lawnmower and just whacked the mother right across the face with it, while she was talking to me.”

“And at that moment, I was thinking: `this kid is on a track for really serious behavioural problems’. I mean, it was already pretty serious right then and there. But there was the thought that if this family could not turn around that propensity of that child to use violence and to escalate in the face of things happening that he didn’t like happening, that both that youngster and that family were on a track for really serious problems down the road.”

“And so it really started me thinking about the issue of, well how many kids like this are out there? And what kinds of services and programmes are accessible to them? And are we doing a good enough job to make intervention support – that I was able to provide to this mother to turn the problem around – available to a much wider range of families?”

What changed for you that day?

“I was already doing research and developing parenting interventions that we now call Triple P, so I was actively involved in both researching solutions but also applying it clinically – in my everyday clinical work. But I think the experiences of seeing these problems in their raw, full-on reality, and to see a mother highly distressed, and embarrassed, because her child had essentially used a weapon to whack her over the face with – while she was trying to talk to a professional about what she was concerned about – that’s a pretty real demonstration of the kind of issues that families confront.”

“And I think sometimes, seeing it first-hand, seeing it directly – to fully appreciate the emotional significance of it, and the meaning of it, for the family, is very important when it comes to thinking about what a solution needs to look like.”

Is it hard to strike the right balance between theory and practice?

“Triple P’s been very much built on hands-on experience and involvement with all of the interventions. So it’s not been this abstract theoretical academic exercise. It’s been very much trialling, testing, and shaping the way in which programmes need to be delivered in order to ensure that they’re effective, and then putting them to the acid test of clinical trials.”

“Yes, there are different levels of scholarship in developing a programme like Triple P, but the solutions that are developed have to be practical, they have to be anchored in the world of realities, they’ve got to be deployable by practitioners, they’ve got to be able to be used by parents in a way that makes sense. And it has to be able to be integrated into people’s everyday lives.”

“Positive parenting is not something you do by doing a parenting programme – it’s something you live and breathe, as part of the way in which your family operates.”

So what happened to that family?

“They did very well. The mother was very receptive to the positive parenting strategies that were introduced. The father was also involved, eventually, in the intervention, and there was a very rapid turnaround in this child’s behaviour. His parents started responding differently to it. Basically this child had become a bully, and his bullying behaviour had been highly effective in getting other people to jump wherever he wanted them to. He got a massive amount of attention for the problem behaviour. He could control the social world of that family just through escalation. And once the mother realised what she was doing, acquiescence was not the name of the game. She needed to remain firm, consistent, and establish boundaries and limits, and above all else, become really good at giving the child positive attention when they were behaving well – so descriptive praise, catching them being good – crucial.”

And the boy – were you able to follow up with them?

“I followed them up for about a year and a half after the intervention, and the effects were maintained – they did well.”

It must have been very satisfying, to see that?

“It was fantastic – one of the things about being a skilled practitioner, doing this kind of parenting work, is that it’s a very rewarding professional activity – because the vast majority of times you’re using the intervention, you’re getting good results. And that’s really gratifying.”

“Most people in this field want to do the right thing by families and get good results. But if you’re not using evidence-based programmes, you’re not using programmes that work – you’re hitting your head against a brick wall, frequently. You’re experiencing a lot of failure, clinically. And that’s demoralising, that makes people feel as though that their work is not valued.”

“But when people acquire evidence-based tools that enable them to work more successfully – there’s huge rewards involved, personally, in knowing that what you’re contributing to children and families is making a difference. And that’s a – that’s a really nice contribution to make.”